Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS) is a condition that affects the digestive tract of horses, primarily involving the stomach. Due to the anatomy and feeding habits of horses, they can be prone to developing gastric ulcers.

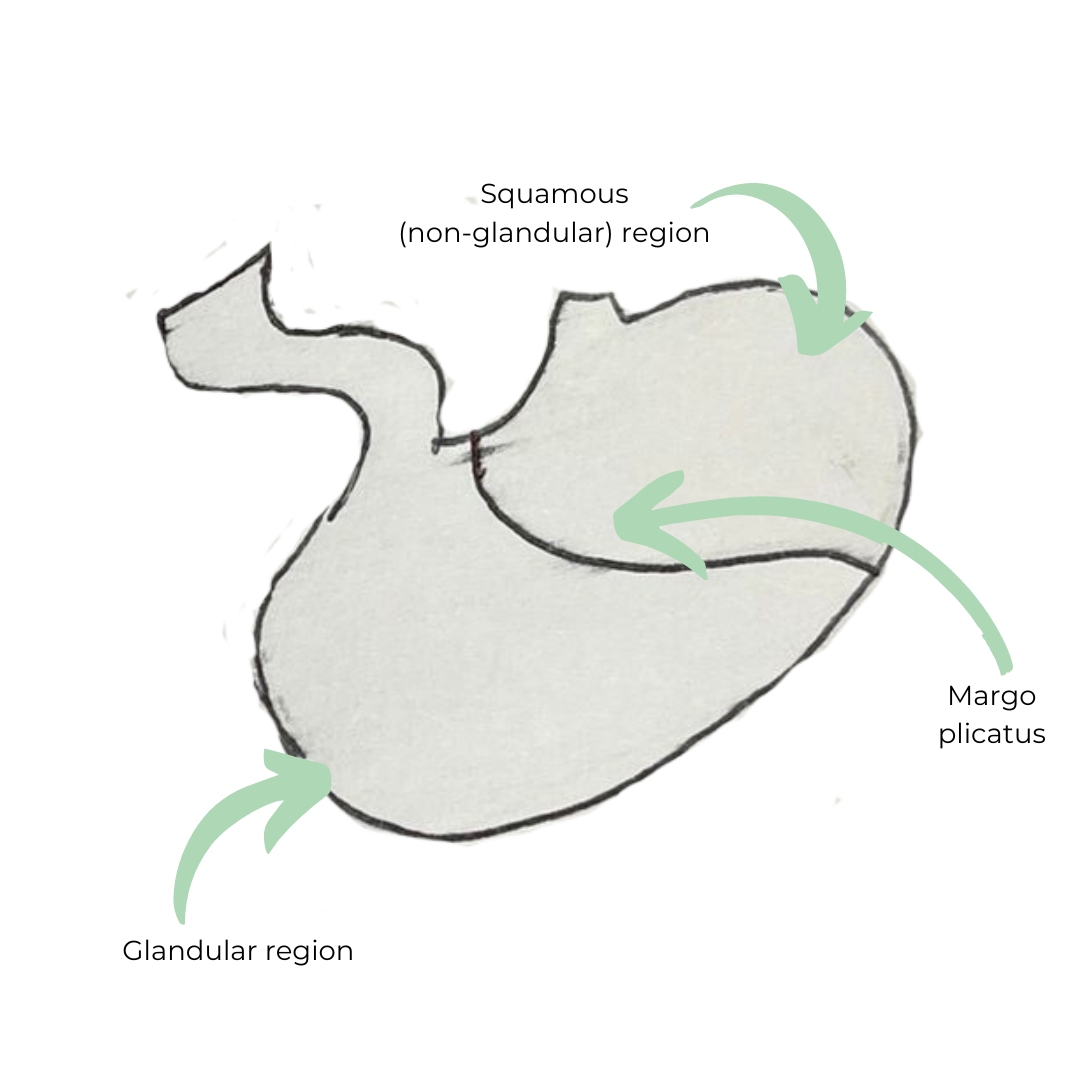

The equine stomach is divided into two main regions: the upper squamous (non-glandular) region and the lower glandular region, as seen in the image below. EGUS can affect both areas, but the majority of ulcers occur in the upper squamous region. The ulcers themselves are often caused by prolonged exposure to stomach acid.

EQUS can occur in feral horses also, however, it is much more prevalent in domesticated equines (Ward et al., 2015). The increased occurrences within domesticated horses is likely down to our management as horse owners.

Typically, the stomach’s mucosa is shielded from gastric acid by a protective layer of mucus. However, if the amount of acid increases or the protective mucus layer is reduced, the underlying mucosa will be damaged. In the horse’s stomach, the upper squamous region is predisposed to erosion and ulcers because they naturally lack the glands to produce mucus (Oaklands Equine Hospital, 2018).

Less-than-ideal management practices, suboptimal feeding, and the use of specific medications can increase a horse’s susceptibility to developing gastric ulcers. These factors include:

- A diet high in grain/low in forage

- Periods of starvation or restricted feed intake

- Stress

- Intensive training

- Certain medications (Oaklands Equine Hospital, 2018).

Symptoms of EQUS

Many horses with ulceration have no obvious clinical signs, or signs that are very subtle and not recognised by owners (Murray et al., 1989). Common signs associated with EGUS include poor appetite, weight loss, poor body conditions, colic and discomfort when tacking up. Alongside the common symptoms, horses can also experience altered behaviour, changes in their coat, teeth grinning and self-mutilation (van den Boom, 2022).

Treatment

Ulcers in horses, especially those in race training, don’t usually get better on their own, they need medical treatment (Murray & Eichorn, 1996). There are cases where ulcers can heal naturally, like when some horses were given time off and showed improvement in 14–25 days. However, using omeprazole made healing happen more often and faster (Murray et al., 1997). Interestingly, when horses with diet-induced squamous ulcers were allowed to graze in a pasture, 55% of the ulcers healed (McGowan et al., 2007).

Prevention

Prevention of EGUS involves providing a well-balanced diet, access to forage, regular turnout, and minimising stressors whenever possible. It’s important for horse owners to be aware of the risk factors and signs of EGUS to ensure early detection and appropriate management. If you suspect your horse may have gastric ulcers, it’s crucial to consult with a veterinarian for a proper diagnosis and treatment plan.

References

McGowan, C.M., McGowan, T., Andrews, F.M. and Al Jassim, R. (2007) ‘Induction and recovery of dietary induced gastric ulcers in horses’, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine [Preprint].

Murray, M.J. and Eichorn, E.J. (1996) ‘Effects of intermittent feed deprivation, intermittent feed deprivation with ranitidine administration, and stall confinement with ad libitum access to hay on gastric ulceration in horses’, American Journal of Veterinary Research, pp. 1599–1603.

MURRAY, M.J. et al. (1989) ‘Gastric ulcers in horses: A comparison of endoscopic findings in horses with and without clinical signs’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 21(S7), pp. 68–72. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1989.tb05659.x.

MURRAY, M.J. et al. (1997) ‘Effects of Omeprazole on healing of naturally‐occurring gastric ulcers in thoroughbred racehorses’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 29(6), pp. 425–429. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03153.x.

Oaklands Equine Hospital (2018) Equine gastric ulcer syndrome, Oaklands Veterinary Centre. Available at: https://oaklandsvetcentre.co.uk/equine/common-diseases/equine-gastric-ulcer-syndrome/ (Accessed: 19 January 2024).

van den Boom, R. (2022) ‘Equine gastric ulcer syndrome in adult horses’, The Veterinary Journal, 283–284, p. 105830. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2022.105830.

Ward, S. et al. (2015) ‘A comparison of the prevalence of gastric ulceration in feral and domesticated horses in the uk’, Equine Veterinary Education, 27(12), pp. 655–657. doi:10.1111/eve.12491.