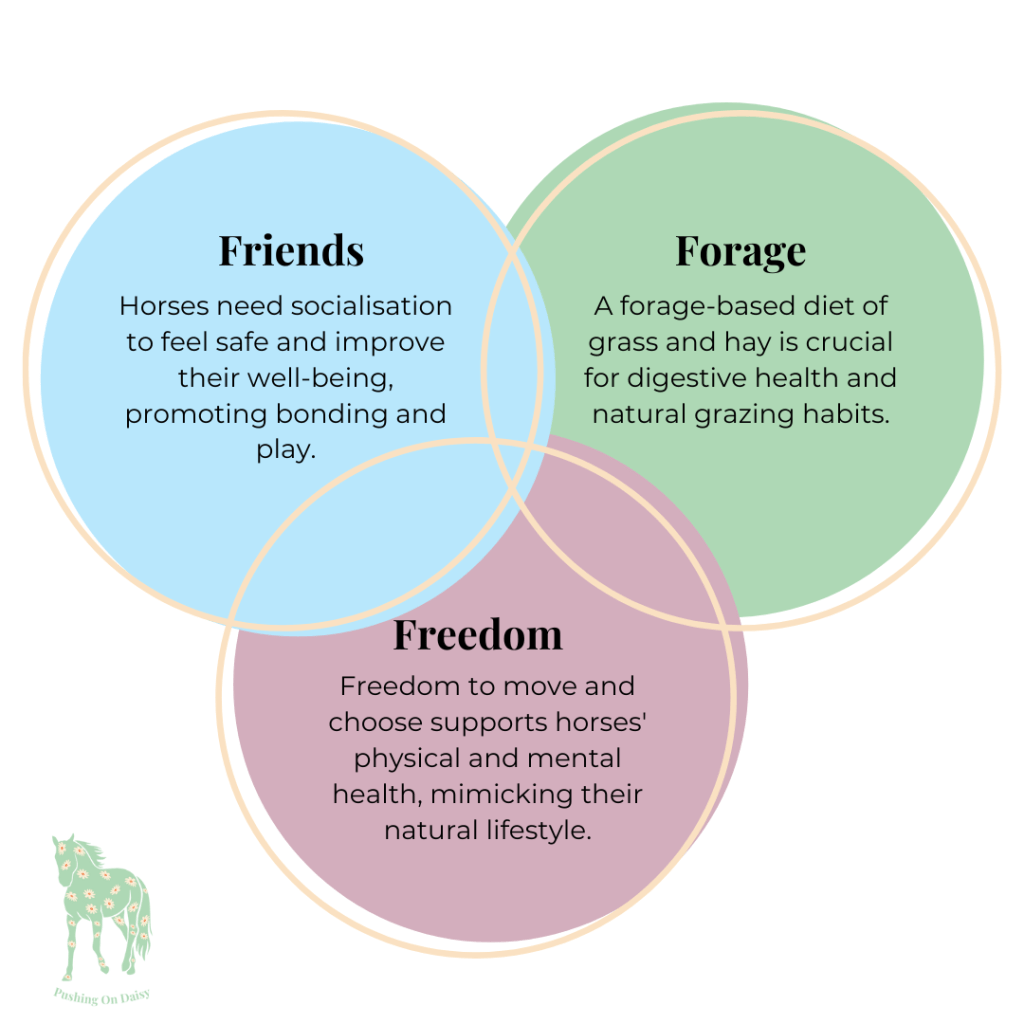

As equestrians, it is our duty to provide the horses in our care with a species-appropriate life centred around their three essential needs: friends, forage, and freedom. Understanding and fulfilling these needs is crucial not only for the physical health of our horses but also for their mental and emotional well-being.

Krueger et al., (2021) investigated the essential environmental requirements for horse welfare, specifically social contact, social companionship, free movement, and access to roughage. By examining 38 studies on horses’ behavioural and physiological responses to these needs being restricted, the researchers categorised reactions into four types: Stress, Active, Passive, and Abnormal Behaviour.

Results showed that restricting combinations of social contact, free movement, and access to roughage led to significant suffering, evidenced by passive responses and abnormal behaviours. The study highlights the importance of assessing both behavioural and physiological parameters in evaluating horse welfare and confirms that social contact, free movement, and access to roughage are indeed basic needs for horses.

Friends: Social Interaction and Herd Dynamics

Horses are inherently social creatures. In the wild, they thrive in herds, forming complex social bonds and hierarchies. Providing domestic horses with companionship can significantly reduce stress and anxiety, leading to a happier and healthier life.

As shown in Hebesberger’s 2023 study, horses generally benefit from being with a familiar horse during mild stress, suggesting that housing horses in groups benefits their welfare. Further studies have also shown that having a companion present helps horses handle stress, but how it helps depends on the type of stress they are facing (static vs startling), allowing greater contextual processing and physiological recovery in response to startling events (Ricci-Bonot et al., 2021; Ricci-Bonot et al., 2021).

Correct management of horses (allowing them to live in herds and graze freely etc) reduces the development of repetitive behaviours called “stereotypies”. The most common examples of these behaviours are crib biting, weaving and box walking. Behavioural changes are often the first clue that an animal is in poor condition. One important type of behaviour to watch for is stereotypic behaviour. Scientists suggest that these behaviours are good indicators of poor animal welfare because both experiments and surveys show a connection between these behaviours and bad environments (Sarrafchi & Blokhuis, 2013).

Forage: Natural Feeding Patterns

Forage is another cornerstone of a horse’s well-being. In the wild, horses graze for up to 16 hours a day, feeding on a variety of grasses and plants. This constant intake of small amounts of food is crucial for their digestive health. Providing a forage-based diet mimics this natural feeding behaviour, promoting better gut health and preventing issues like colic and ulcers. Studies have shown that incorporating more fibre and carefully managing the types and timing of feeds can help maintain the health and performance of horses (Cipriano-Salazar et al., 2019).

When horses lack sufficient foraging opportunities, they may develop behaviours that mimic foraging, often due to the need for the activity itself rather than fibre intake. Even horses on fiber-rich diets may exhibit such behaviours if their foraging needs are unmet. Replacing starch in a horse’s diet with fibre can significantly improve digestion, health, behaviour, and performance while reducing the risk of gastrointestinal issues.

For horses in intense work that require concentrates, it’s best to divide their daily feed into at least three meals, ideally four to six. This approach aligns better with their natural “little and often” feeding physiology. If hay isn’t provided freely, offering some before their hard feed will help increase forage intake and hopefully, slow down the eating of the concentrate (Lawrence, 1995).

Freedom: Space To Move & Explore

Freedom to move is essential for horses’ physical and mental health. In the wild, horses roam over large areas, engaging in various activities that keep their bodies and minds active. During Schoenecker’s et al., (2022) study of feral horses from two locations in Utah, they found that on average, horses’ “home space” was about 38.61 to 46.33 square miles.

Providing opportunities for movement helps maintain their physical fitness, prevents boredom, and allows for natural behaviours like running, rolling, and playing. Not only that, but studies have shown that giving horses turnout after training, appeared to reduce stress and improve their willingness to perform, compared to keeping them in stalls without turnout (Werhahn et al., 2012).

Horses with access to turnout also maintain better fitness and experience greater improvements in bone mineral content compared to their stabled counterparts, highlighting the critical importance of turnout (Graham-Thiers & Bowen, 2013).

Conclusion

By focusing on the Three Fs—Friends, Forage, and Freedom—we can create a more natural and fulfilling life for our horses. Providing social interaction, a forage-based diet, and ample space for movement not only enhances their physical health but also supports their mental and emotional well-being. As caretakers, it’s our responsibility to strive for the best possible quality of life for these our animals. Embracing these principles ensures we meet the fundamental needs of our horses, encouraging a harmonious and happy partnership.

References

Cipriano-Salazar, M. et al. (2019) ‘The dietary components and feeding management as options to offset digestive disturbances in horses’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 74, pp. 103–110. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2018.12.017.

Graham-Thiers, P.M. and Bowen, L.K. (2013) ‘Improved ability to maintain fitness in horses during large pasture turnout’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 33(8), pp. 581–585. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2012.09.001.

HEBESBERGER, D.V. (2021) ‘Benefits of social bonds in domestic horses (Equus caballus): The effect of social context on behaviour and cardiac activity’, A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy [Preprint].

Krueger, K. et al. (2021) ‘Basic needs in horses?—a literature review’, Processing of environmental stimuli and farm animal welfare, 11(6), p. 1798. doi:10.3390/ani11061798.

Lawrence, L. (1995) ‘Equine Feeding Management: The How & When of Feeding Horses’, Department of Animal Sciences [Preprint].

Ricci-Bonot, C. et al. (2021) ‘Social buffering in horses is influenced by context but not by the familiarity and habituation of a companion’, Scientific Reports, 11(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88319-z.

Ricci-Bonot, C. et al. (2023) ‘An inconsistent social buffering effect from a static visual substitute in horses (Equus Caballus): A pilot study’, Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 67, pp. 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2023.07.004.

Sarrafchi, A. and Blokhuis, H.J. (2013) ‘Equine stereotypic behaviors: Causation, occurrence, and prevention’, Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 8(5), pp. 386–394. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2013.04.068.

Schoenecker, K.A., Esmaeili, S. and King, S.R. (2022) ‘Seasonal resource selection and movement ecology of free‐ranging horses in the Western United States’, The Journal of Wildlife Management, 87(2). doi:10.1002/jwmg.22341.Werhahn, H., Hessel, E.F. and Van den Weghe, H.F.A. (2012) ‘Competition horses housed in single stalls (II): Effects of free exercise on the behavior in the stable, the behavior during training, and the degree of stress’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 32(1), pp. 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2011.06.009.